An interstitial approach for religious harmony in India

Introduction

The global political reality today is one of identitarian and communal violence. This is especially true for India, where communal identity has become the fertile ground for violence and exclusion. Cultural nationalism – perched on state power and authority – fuels this violence and exclusion by the creation of a monolithic Hindu identity, politically crafted from a distorted narrative of the cultural history and geography of India. Everything that falls outside this monolith is deemed, to that degree, un-Indian. I argue that the political reality of India today is one of violent identification. This forming of national identity, cleansed of internal fissures and ambiguities, is itself violence. Epistemology here directly entails violence. This is not a mere abstraction, for the engineering of an unambiguous national and religious identity – often marrying geography and religion – has led in the last couple of years to such deeply harmful legislations as the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) and the National Register of Citizens (NRC); laws directly targeting India’s Muslim minority, which is always left negotiating its place and participation in the monolithic nationalist narrative.

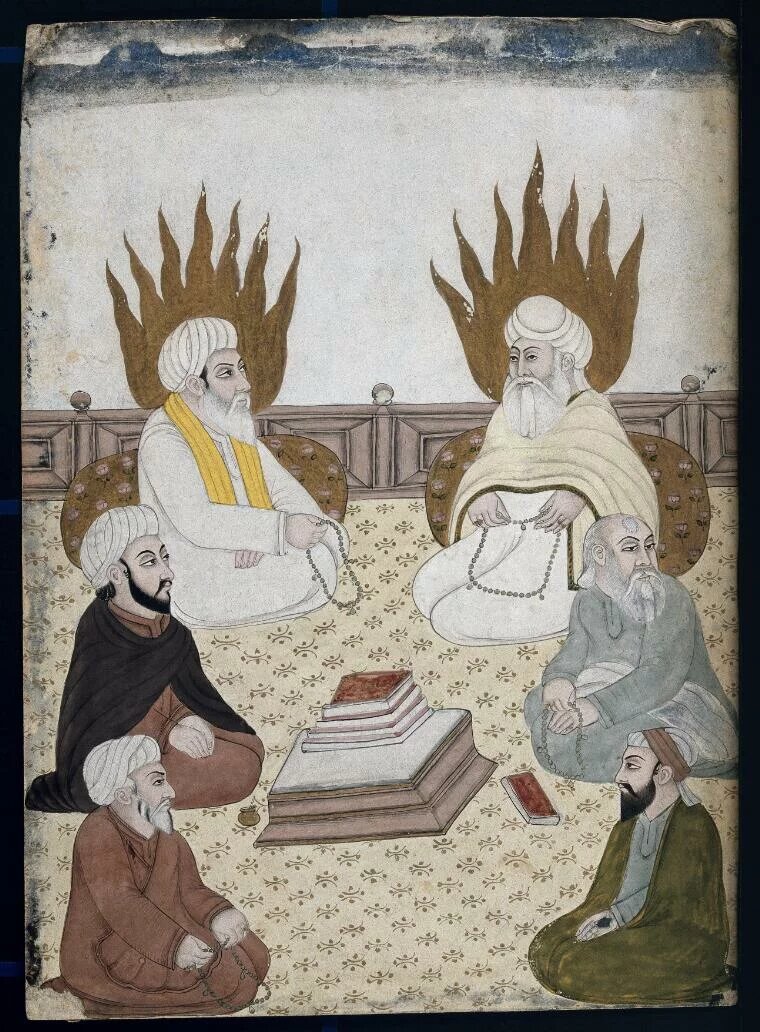

This essay intends to play with the concept of identity and its often entrenched and fixed nature. Non-violence and peace, mutual understanding and inclusivity, it argues, can result only from ambiguous, in-between identities. In opposing the epistemology of identitarian violence, I look for resources among the Sufis – from within and without India – like Ibn ‘Arabī (who gives us a metaphysics and epistemology of paradox and in-betweenness), Dārā Shikōh and Sarmad Kāshānī (the deepest historical expressions of interreligious imagination).These Sufi mystics and poets understood the violent jealousy of borders and so they aimed, in the words of Dārā Shikōh, to etch lines of demarcation in water rather than in stone. They have much to teach us in our troubled times today about navigating our political landscapes of violent identifications.

Knots of identity

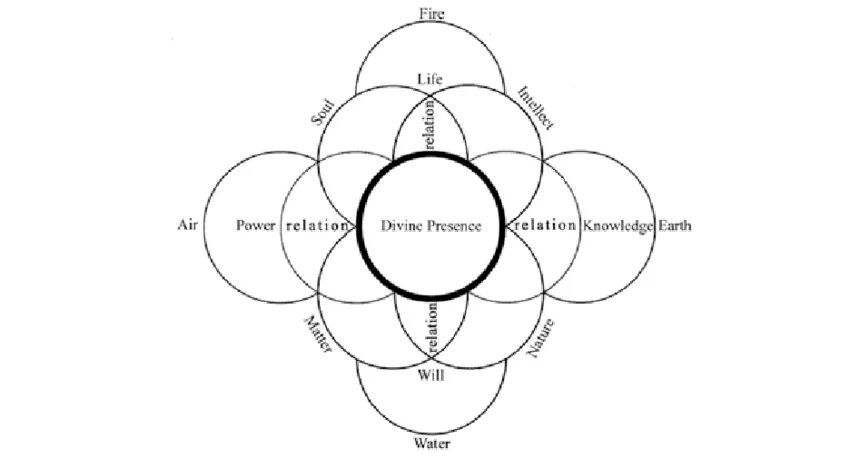

Ibn ‘Arabī understands faith in terms of knots; to believe in something is to tie a knot in the heart (Chittick 1989, 335-352). It is to fix one aspect, from an infinity of possible ones, and make it the object of one’s religious concern. To fully grasp the meaning of belief as knot (aqd), one must pay closer attention to his overall ontology. Ibn ‘Arabī’s ontology is called wahdat al-wujud, literally translated as the Unity-of-Being. It could be succinctly defined as a metaphysics where all of reality is nothing but Being (wujud) itself. This immediately raises the question of the “manyness” of reality. If there is only Being, whence beings and entities in their variegated diversity? This problem is not dissimilar to the one that the schools of Vedanta have historically wrestled with.

For Ibn ‘Arabī, the cosmos – reality in all its modes – is both One and Many. The variegated cosmos is the pluri-form manifestation of one underlying Reality. As remarked above, the problem of the One and Many is a persistent one in the history of religion and mysticism. In Ibn ‘Arabī’s school, the variegated cosmos is nothing but the endless self-disclosure of the One as the Many. The One Reality or Essence shows itself by hiding as the many, effectively veiling itself through its unveiling.

The Real manifests itself only “from veil to veil” (Chittick 1989, 230), with none of these manifestations being the final disclosure of the Real. There can be no veil that is also not simultaneously a window into the Real; and there can be no window or opening into the Real, which does not simultaneously veil this sheer plenitude. This paradoxical (and apparently contradictory) intertwining of veiling and unveiling is a crucial trope in Sufi poetry and metaphysics. Ibn ‘Arabī quotes al-Kharrāz saying, “God cannot be known except as uniting the opposites” (1980, 85).

God is both transcendent from the cosmos and immanent in it. In more direct terms, Ibn ‘Arabī calls the cosmos He/ Not He. Therefore, every object of belief – any concept or thing that purports to represent God – is a modality of God’s manifestation; and all objects of beliefs are ways in which the Real (al-Haqq) manifests Himself while also transcending from them all. Here is a quintessential definition of belief in Ibn ‘Arabī: “The root of the diversity of beliefs in the cosmos is this manyness in the One Entity” (Chittick 1989, 338). All beliefs about God then are, in the ontological sense, true – because they cannot be anything but the manifestations of the Real for “wheresoever ye turn, there is the face of Allāh” (Quran 2:109). Yet, in another sense, every human belief (or faith construction) about God is insufficient, for God is infinitely excessive of anything that can be said or believed of Him.

It is this interplay of God’s inmost immanence and his incomparable transcendence – his immanence as the transcendent and his transcendence as the immanent – that makes Ibn ‘Arabī say: “He who is more perfect than the perfect is he who believes every belief concerning Him. He recognises Him in faith, in proofs, and in heresy” (Chittick 1989, 349). It is also the basis of Dārā Shikōh’s opening statement in his Majma-ul-Bahrain (Mingling of the Two Oceans): “Abundant praise be (showered) on the Incomparable One, who has manifested on His beautiful, unparalleled, matchless face the two parallel locks of Faith (Iman) and Infidelity (Kufr), and by neither of them has He covered His beautiful face” (1998, 37).

However, Ibn ‘Arabī is not preaching a New-Age ‘anything goes’ spirituality. Rather, his metaphysical position allows us to understand that in all matters of identity, there is always an excess, which no single doctrine or belief can fully capture.

In his classic text Anti-semite and Jew, Jean-Paul Sartre defines a bigot as someone exclusively attached to a particular content of truth while being afraid of the form of truth, which is an infinite process of finding. The bigot is fanatically attached and restricted to a particular knot in the heart (to use Ibn ‘Arabī’s vocabulary), while being petrified of the plenitude of Being that transcends this knot. To quote Susanne Claxton from her work Heidegger’s Gods: An Ecofeminist Perspective, “The anti-semite or bigot, for Sartre, is someone who wishes to be in possession of complete and immutable truth because he simply cannot deal with the prospect of the truth not being finite” (2017, 17). This is not, however, a call to relativism and shirking of all commitment to a particular belief or identity; it is rather a call to embrace these commitments with responsibility and sensitivity to the infinite possibilities that lie beyond these discrete commitments.

Lines on water: Dārā Shikōh-Sarmad Kāshānī

We saw that for Ibn ‘Arabī the world is He/ Not He; it is in fact the slash between He/ Not He. This fuzziness of borders, interstices, and lines in-between Ibn ‘Arabī calls barzakh. Bruce Lawrence captures Ibn ‘Arabī’s metaphysical position as the irreducibility of the in-between (2020, 459). Barzakh logic, Lawrence argues, makes the borders the epistemic source of knowledge and engagement. Barzakh represents the negative space between two entities while being associated with neither. It is through this space of difference between A and B that the identities of A and B are established. But the difference itself – the space in-between – is not reducible to sensible or rational or imaginal explanations. It is the sheer irreducible mystery of the interpenetration of the One/ Many, the He/ Not He.

The mystery of this slash between self/ other, transcendence/ immanence is what constitutes existence itself; and the irreducibility of this to any final rational demonstration makes Ibn ‘Arabī say that “[True] guidance means being guided to bewilderment, that he might know that the whole affair [of God] is perplexity, which means perturbation and flux, and flux is life” (1980, 254). It is this hermeneutics of the in-between, of difference, and of the excess of paradox and perplexity that should guide us today in our engagement with religious tolerance, dialogue, and the knots of belief.

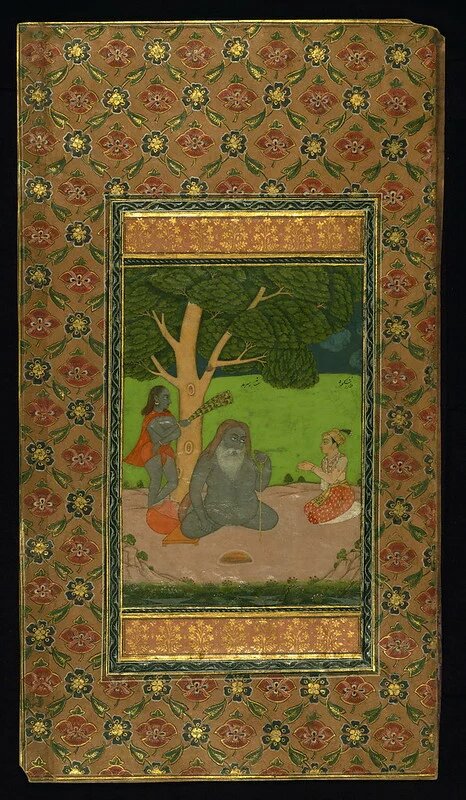

Prince Dārā Shikōh (d. 1659) represented this hermeneutics of difference in his engagement with the different religious worlds of seventeenth century Mughal India. We shall here look at two dialogue partners of the prince: Lāl Dās and Sarmad Kāshānī. First, however, we should note that Ibn ‘Arabī’s wahdat al-wujud influenced Indian Sufism immensely and was a major framework for this cultural fermentation and Hindu-Muslim dialogue.

Dārā Shikōh held discussions with Lāl Dās repeatedly from 1652 to 1653 at Lahore. A little-known manuscript called Su’āl va Javāb details the many questions that Dārā posed to Lāl Dās (Heyat, 2016). What is evident in Dārā’s questions to the Hindu ascetic is both the genuine desire for understanding the truth, and the commitment to the form of truth rather than just the knot of particular beliefs. His approach is the same as in his Majma-ul-Bahrain where he treats both the traditions (of Sufism and Vedanta) as “two truth-knowing groups” (1998, 38). Even as he asks Lāl Dās about the worship of idols, he is genuinely inquisitive. Lāl Dās’ response that the idols are preliminary supports for concentration of mind seems to convince the prince. His questions evince a strong grasp of the various religious beliefs of the subcontinent. For him, though the two religious traditions represent different knots in the heart, the underlying Reality the knots are trying to capture is the same. The prince’s feeling about these meetings is recorded in his Samudra Sangama in these words:

“I attained peace along with other altogether perfect Vedic seers, especially in nearness to the true guru, an image of the form itself of spirituality and of knowledge Bābā Lāl, who by the Lord, has attained the utmost askesis, of knowledge, of the fruit of right understanding, and with him I met and conversed frequently” (2016, 62).

Dārā Shikōh’s interreligious approach is captured by his metaphor of “drawing a line on water” when asked during his trial to draw boundaries between religions (Kent 2013, 3). Such a demarcation of identity maintains itself by being simultaneously subject to imminent shifting and erasure. This metaphor comes remarkably close to the notion of barzakh, the ever-shifting in-between.

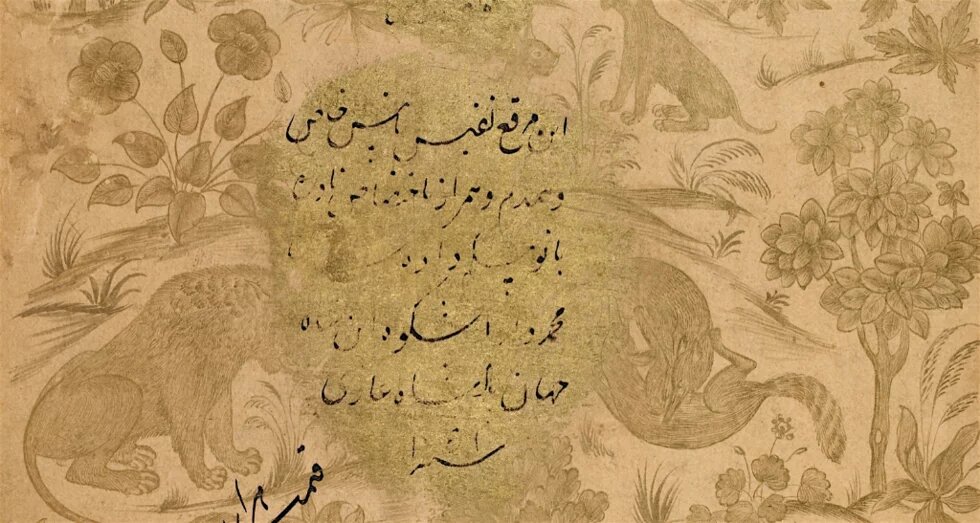

Dārā Shikōh also met Muhammad Sa’id Sarmad Kāshānī (d. 1661) and was immediately attracted to his charisma and teaching. Sarmad Kāshānī was a Jewish-Armenian-Sufi-Yogi whose identity was always drawn on water – always collapsing and re-forming. Not only was his religious and spiritual identity drawn on water, but so was his body, his very appearance (as clothed in nakedness) and his sexual orientation (with his romantic-spiritual love for the Hindu Abhay Chand). Sarmad physically embodied a barzakh identity. This embodied paradox shows quite strongly in his verses. For instance, he says (1991, 73):

“I love madness, dynamism, but I am not distraught,

An infidel, an idolater,

I am not one of the pious.

I am going towards the mosque,

But I am not a Muslim.”

The Sufi is always on the way. Unlike the metaphysician or theologian who has finally captured the Real, the Sufi embraces the perplexity of constant dynamism. This being ever on the way and never quite arriving is epitomised in the last days of Sarmad’s life where he is tried for infidelity at the Mughal court. When asked to recite the testimony of faith, Sarmad only recites the first half (‘There is no God’) and declares that he has not quite arrived at ‘But God’ and so to recite that would be to lie. And yet Sarmad’s poetry, paradoxically, also reflects a profound sense of Muslim piety. For instance (1991, 67):

“You desired happiness

But only in this world.

You did not entreat God

For happiness in the other world.

At once you lost

Both worlds

And all you were left with was

Lifelong repentance.”

How do we explain this paradox? What Sufis like Sarmad are teaching is the holding of an identity while at the same time being fully present to the mystery and paradox of all identities. It is the recognition that difference in some sense precedes identity. And as Ibn ‘Arabī teaches, without a thing’s being different from the other, it would not be the thing that it is; meaning, the Other is a fundamental constituent of all selfhood. Selfhood happens in-between, in the interstices of plural possibilities. This does not mean that Dārā Shikōh or Sarmad Kāshānī renounced their Muslim identity; rather their Muslim identity was pluri-form enough to allow room for other identities and for the recognition of other “truth-knowing” paths.

It is with this in mind that we should read verses like these in Sarmad (or Abhay Chand; the ambiguity of authorship is itself interesting) (Harris 2015, 221):

“I follow the Koran as much as I follow Torah and Talmud

But I am neither a Jew nor a Christian nor a Muslim.”

The Sufi heart is a heart that can take any form, for this is the religion of love (din al-hubb; mazhab-i-ishq). We saw above that the Sufi is always on the way to the truth, and never finally and securely there. This sensitivity to non-finality – to the infinite form of truth – is what makes the Sufi’s heart take many forms and recognise and empathise with the spiritual struggles in other traditions and paths. To end with a verse of Ibn ‘Arabī’s from his Tarjuman al-Ashwaq (2021, 39–41) that epitomises this “religion of love”:

“My heart can take on

any form

For gazelles a meadow

A cloister for monksA temple for idols,

pilgrim’s Ka`ba,

tablets of Torah,

scrolls of the Qur’ân

I profess the religion

of love Wherever

its camels turn, there

lives my faith.”

In an age of violent identification, the Sufis teach us the virtue of bewilderment, water-drawn demarcations, and to hold our hearts in living flux, ready for any form. Imbibing these teachings and recognising the place of the Other in the formation of one’s self-identity is the difficult political and cultural challenge today.

References

Chittick, William.1989. The Sufi path to knowledge: Ibn al-Arabi’s metaphysics of imagination. SUNY Press.

Claxton, Susanne. 2017. Heidegger’s Gods: An ecofeminist perspective. Rowan & Littlefield.

Lawrence, Bruce. 2020. Writing in the eye of the storm. Critical Times 3, no. 3 (December): 456–463.

Harris, Jonathan Gil. 2015. The first Firangis: Remarkable stories of Heroes, Healers, Charlatans, Courtesans & other foreigners who became Indian. Aleph.

Heyat, Perwaiz. 2016. The conversation between Dārā Shukōh and Lāl Dās: A Șūfī-Yogī dialogue of the 17th-century Indian subcontinent. McGill University (PhD thesis).

Ibn ‘Arabī. 1980. The Bezels of wisdom (Trans. Ralph Austin). Paulist Press.

Ibn ‘Arabī. 2021. The translator of desires: Poems (Trans. Michael Sells). Princeton University Press.

Kent, Eliza and Tazim Kassam. 2013. Lines in water: Religious boundaries in South Asia. Syracuse University Press.

Muhammad Dārā Shikōh. 1998. Majma-ul-Bahrain or the mingling of the two Oceans (Trans. M. Mahfuz-ul-Haq). The Asiatic Society.

Sarmad Kāshānī. 1991. The Rubaiyat of Sarmad (Trans. Syeda Saiyidain Hameed). The Indian Council for Cultu

Disclaimer: This article was prepared with the support of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung India. The views and analysis contained in the publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung/and the author's affiliated institution.